“For You Know Neither the Day nor the Hour”

As the days shorten, the nights lengthen, and we see the end of the calendar year drawing nigh, we are reminded of the end of yet another year: the Church year. Since the new liturgical year begins roughly four weeks before Christmas, it also comes to an end sometime in late November on the Last Sunday of the Church Year.

A day of transition from one year to another, this Sunday is memorable for many in the Church because it is dedicated to another transition: the transition from this old world to the new heavens and the new earth on the Last Day. With this intense focus on the end of all things, the Trinity season, which begins shortly after Pentecost and runs through the rest of summer and fall, comes to a close.

The Trinity season is not largely dedicated to any particular observance or Church holiday, with the Sunday propers rather focusing more generally on the meaning of Christ’s resurrection within our ordinary lives. However, in the days after Michaelmas at the end of September—and especially in the time following All Saints’ Day—the flavor of the Sunday lessons decidedly changes. They seem to focus on a more sobering reality, centering increasingly on themes like death, judgment, and the conclusion of all things.

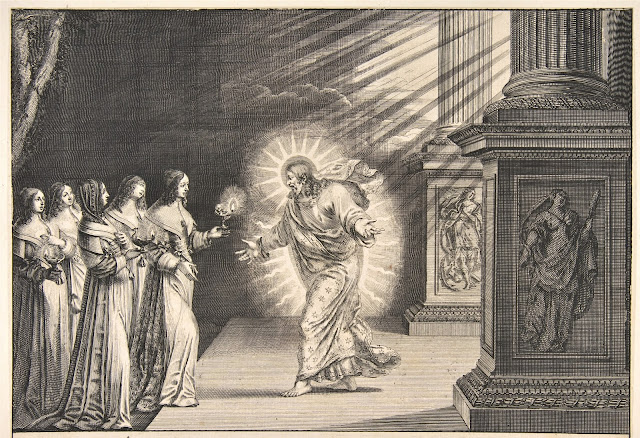

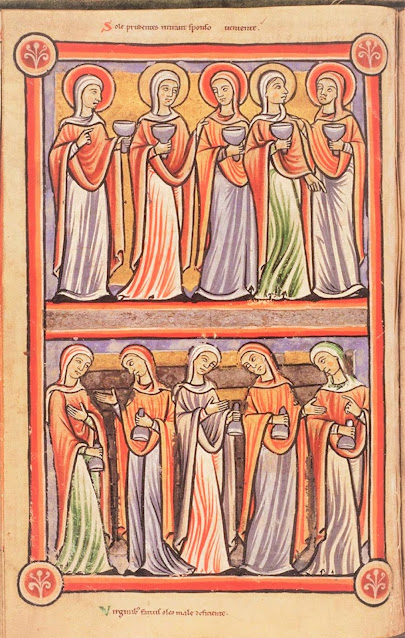

We are finally brought to the Last Sunday of the Church Year, where both the Epistle and the Gospel lessons describe Christ’s future coming in judgment and the importance of a sober-minded watchfulness in the Christian life. Specifically, the Epistle comes from St. Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, where he warns them that Christ will arrive “like a thief in the night” (1 Thessalonians 5:1–11) and exhorts them to watch for his coming, much like the Gospel lesson contains our Lord’s Parable of the Ten Virgins, ending with his admonition to “Watch therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour.”

These lessons presage the Sundays of Advent, where the lessons highlight the Lord’s coming in mercy for his people. In this way, the end of the Church year somewhat mimics the transitional purpose of Gesimatide: both of these transitional periods in the Church’s calendar prepare Christians for the penitential seasons that follow them.

For Lutherans, this heightened focus on the end times and eschatology carries with it notes of both law and gospel: an awareness of both the final judgment and the promise of a new heaven and new earth. As the Rev. Professor John Pless reminds us in his article, “The Last Sundays of the Church Year,” it brings our attention to the end of the Nicene Creed’s second article: “And He will come again with glory to judge both the living and the dead.”

A Brief History

While it is difficult to point with certainty to the moment when the Last Sunday of the Church Year assumed its current liturgical form, it is safe to say that it has been celebrated much as it has today since sometime in the Middle Ages. In the Early Middle Ages, the season of preparation for Christmas was frequently much longer than it is today in the West, lasting around forty days from early November until December 25. Over time, however, that season became shorter in the West until it became the roughly four-week Advent season we know today. This development took place within the Western Church well before the Reformation, by which point the Church year came to a close before this shorter Advent season.

While the observance of the Last Sunday of the Church Year as it is found in the Historic Lectionary was largely fixed in the Middle Ages, several other more recent developments within the Western Church have also shaped the way in which it has been celebrated in Lutheran and non-Lutheran churches. For example, in the nineteenth century, Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia ordered that the day be set aside for remembering the dead, much as many Lutheran Churches today commemorate the faithful departed on All Saints’ Day. This practice spread within many German-speaking churches, where the day is often called Totensonntag (Sunday of the Dead) or Ewigkeitssontag (Eternity Sunday). The day has also been called Judgment Sunday among many Nordic Lutheran churches, a name that reflects the themes of its propers.

Perhaps the most recent development that is worthy of note is that of Christ the King Sunday, a holiday that was instituted in the Roman Catholic Church by Pope Pius XI in 1925 as a response to the secularism of the twentieth century. This commemorating supplanted the historic Last Sunday propers in the Roman Catholic Church and was subsequently adopted by many Protestant churches, as well. As a result, usage of the older Last Sunday propers has receded in much of the Western Church, even as it has remained among Lutherans who continue to follow the Historic Lectionary.

Collect

Absolve, we beseech Thee, O Lord, Thy people from their offenses: that from the bonds of our sins which by reason of our frailty we have brought upon us, we may be delivered by Thy bountiful goodness; through Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with Thee and the Holy Ghost: ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Lessons

Resources

Issues, Etc. interview with the Rev. Michael Frese on the Parable of the Ten Virgins

Issues, Etc. interview with the Rev. David Petersen on the Last Sunday of the Church Year

Propers found in Daily Divine Service Book: A Lutheran Daily Missal, edited by the Rev. Heath Curtis

References:

1. Blackburn, Bonnie and Leofranc Holford-Stevens. The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford University Press. 1999.

2. The Rev. Professor John Pless, “The Last Sundays of the Church Year,” 1517.

Images:

1. The Wise Virgins Before Christ, Abraham Bosse, France, 1635.

2. The Wise and Foolish Virgins, From “A Picture Bible,” France, c.1990-1200.

3. The Wise and Foolish Virgins, Godfried Schalcken, The Netherlands, c. 1700.

Some links might be affiliate links which means we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.