Introduction

“And when you pray, you must not be like the hypocrites. For they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, that they may be seen by others. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will reward you.”

Matthew 6:5-6

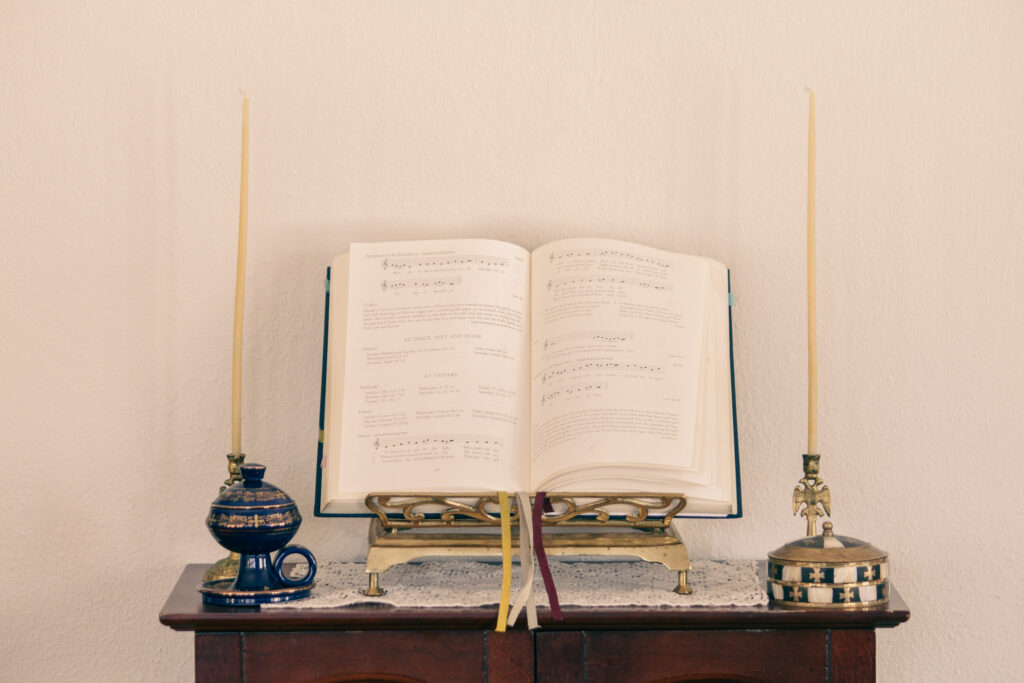

In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives these instructions and encouragement regarding prayer, one activity in which the Church increases during her Lenten journey along with fasting (about which we go into detail here) and almsgiving. When talking about prayer, especially during Lent, it is only fitting to talk about the daily structure of prayer the Church has offered her people from the very beginning. From the earliest centuries, Christians have taken to her Lord’s invitation to pray to our Father in heaven who hears our prayers. This is expressed in spontaneous prayer but is also found within the structure of the day’s hours as ordered around and sanctified by Jesus’ earthly life. This structure came to be known as the daily office.

“The Daily Office has given voice to the daily prayers of the faithful in ‘many and

various ways’ over the centuries.”

– the Rev. Dr. Paul Grime

The Daily Offices

Lutherans are careful to guard the Divine Service as the chief service of the church, and rightly so because it is the one Jesus commands himself in his last testament. But the Lutheran Church has also carried on the tradition of the secondary services, which are prayed in private or at times by saints gathered in one place. These smaller services are known as the daily office. Each service, roughly assigned to a time of day and shorter in nature than the Divine Service, is comprised of opening verses, psalm(s), hymn(s), reading(s), responsory, and prayers. The fuller offices such as Matins and Vespers feature a canticle and even a spot for a homily or catechetical instruction if desired. The term daily office calls to attention the rhythm each day has of its own: sunrise to sunset, and the duty performed at specific times.

Historical Development

Jesus’ Own Prayer

The daily office finds its times patterned after Jesus’ life. First and foremost are the morning and evening offices. The Psalms speak of praying morning, noon, and night, a pattern established in the Old Testament when these times coincided with morning and evening daily sacrifices. Jesus himself patterned his prayer in a similar way. While he is frequently found in the Gospels holding discourse with his Father at many different times of day, the evangelists note how Jesus was often found praying at the break of a new day and from the daytime into the night. This observation caused one theologian to note, “Jesus, who sanctified all time, was fond of praying during the transition from night to day and day to night. Thus, by way of sanctifying the structure of time, Jesus prays during the two daily transitions of light and darkness” (Reardon).

Expansion of Offices

Added onto the morning and evening services are another layer of offices that fall at the third hour (Terce, 9 am), sixth hour (Sext, 12 pm), and ninth hour (None, 3 pm) – more on the significance of these times below. Finally, we find references to two more times in Hippolytus’ Apostolic Tradition: midnight as the hour of the bridegroom’s return, and the hour at which the rooster crows. Compline is also added onto the list to make a total of eight offices. While the times at which these offices were observed, especially some of the later additions, varied, these eight services formed the formal prayer life of the church early on and were the common thread running through all prayer structures from the cathedral to the monastery.

Cathedral and Monastic Prayer

After the legalization of Christianity under Constantine, the practice of gathering to pray, which was previously necessarily discreet, could now occur openly, allowing the Church’s prayerful expression to flourish. The development was two-pronged: on the one hand there was the greater and grander public worship where the daily office, always intended for the piety of all Christians, became available to all in the cathedral.

On the other hand, there was the monastic side, which pulled away into its own communities—some within the city, others into geographical seclusion—out of which the monastic rules emerged. The Order of St. Benedict is one such rule. One distinguishing factor between the offices of the cathedral and the monastics was the number of psalms prayed at each office. For the greater public, each office might have between one and five psalms fitting for the time of day, whereas the monastics prayed the entire psalter within one day, week, or month, depending on the monastic rule.

At the height of the Middle Ages, the office had been through so many revisions and rules that its intended purpose was largely lost. The rites were not in the common language, the music was incredibly advanced, and the Scripture readings were shortened to accommodate for lengthy legends, taking the focus off of their original intent.

Lutheran Reform

Reforms to the office were well underway when Martin Luther came on the scene, but his contribution struck a chord and drastically changed the emphasis of these daily prayers. First, he emphasized how the prayer hours are not just for the monks but also for the ordinary Christian. Luther also favored the morning and evening services as the hinges for the day, which gave rise to his exhortation to rise and say the Creed, Lord’s Prayer, and his morning prayer. Likewise at night he instructed Christians to say the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and his evening prayer. He also desired that the office be prayed in a language the people present could understand. This means that some daily offices in schools remained in Latin, even as the prayers were translated into other local languages in other settings.

Luther’s reform took hold with many during the Reformation, but one major hiccup between his time and ours was the transition of these ideas and materials to the New World. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the Lutheran Church on American soil had a translated Matins and Vespers, and they weren’t in common use until the twentieth century. Today, our Lutheran Service Book contains Matins and Vespers, Morning Prayer (a compilation of Matins, Lauds, and Prime) and Evening Prayer (a compilation of Vespers and Compline), Compline, and three shorter offices for morning, noon, early evening, and late evening.

The Eight Services

Now that we’ve supplied some of the history behind these services, here is a quick breakdown of each one and the approximate hour at which it might be held.

Vigil

One of the latest additions to the daily offices, the vigil takes place at midnight in expectation for the return of the bridegroom.

Matins/Lauds

The offices of Matins and Lauds can be prayed consecutively, or in some places were morphed into one. This is the principal morning office prayed upon waking. Matins traditionally includes Psalm 95 and either the Te Deum or Benedictus depending on the day and season in the Church year.

Prime

Prime is prayed at the first hour of the day (roughly 6 am) and was likely a later addition. It is a shorter office beginning with Psalm 70:1, a hymn, three psalms, a lesson, and ending with prayers as is the case with Terce, Sext, and None.

Terce

Terce is prayed at the third hour which is 9 am, the hour during which the Holy Spirit descended on Pentecost. It is one of the shorter offices with opening verses, psalms, a hymn, reading, and prayers.

Sext

Sext takes place at noon, the sixth hour. It falls at this time in remembrance of the hour at which our Lord was nailed to the cross. Sext follows the same pattern as Terce.

None

The hour at which Jesus handed over the Spirit and was taken down from the cross. The Wednesday and Friday station fasts would traditionally end at the conclusion of None. This office follows the pattern of Terce and Sext.

Vespers

Vespers is to be prayed in the evening, ideally at sunset. Vespers was also attached to the fasting discipline in some places where the first meal couldn’t be eaten until after this office. Similar to Matins, this service is more built out with opening versicles, psalms, reading(s), the Magnificat canticle, and the prayers.

Compline

Compline is the last prayer, taking place immediately before bed. The word itself is derived from the Latin word meaning completion. Compline is the one service in the Lutheran Service Book, outside of the Divine Service, that includes confession and absolution, of which it is good to make frequent use. The service also includes the Nunc Dimittis, which in the Lutheran Service Book is only found here and in two other places: in the Divine Service immediately following the Lord’s Supper and in the funeral service. Here, it is a confession that “asleep, we may rest in peace” as a daily rehearsal of little slumber until the final sleep of death.

Praying the Offices

Christians rejoice to pray to their Father in heaven, and by it they join Jesus, who invited all into communion with him. The daily office offers a historical structure in which to order not only prayers but also our entire days around the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The history of the daily office reminds us that it is not to become a burden, and we don’t recommend praying all of the services every day, though the hours can be a reminder to pray.

If having a daily habit of morning and evening prayer has been difficult in the past (we know it can be for everyone!), Lent is a perfect time to put the extra effort into figuring out a way to hold consistent morning and evening prayers. And if one already has a habit of morning and evening prayer, perhaps working one of the other shorter prayer offices such as Sext into the day would be a worthy endeavor. Prayer and fasting go hand-in-hand, so if you abstain from a noon-time meal, the lunch hour becomes a perfect opportunity for prayer.

Luther encouraged a return to the cathedral offices, and so we also encourage anyone who is able to attend the services your church might offer during Lent: Lenten Vespers, Evening Prayer, and of course the Divine Service, if offered!

Resources:

1. Kind, David. Oremus: A Lutheran Breviary. 2015.

2. Reardon, Patrick H. The Jesus We Missed: The Surprising Truth About the Humanity of Christ. Thomas Nelson. 2012.

3. Lutheran Service Book: Companion to the Services. Edited by Dr. Paul Grime. Concordia Publishing House. 2022.