Servant of the Poor and the Church

When we look at the saints from the first few centuries of the Church who are commemorated on our calendars, St. Martin stands out as one of the earliest to be celebrated with a feast day without receiving the crown of martyrdom. This fact alone is enough to tip us off that when we look at St. Martin, we are looking at someone who was held in very high esteem by the early Church.

Born in the early fourth century in modern-day Hungary, Martin was the child of pagan parents, his father having served as a soldier in the Roman army. At the age of ten, he defied his parents’ wishes and began attending the Christian church, becoming a catechumen (someone who is being prepared for baptism) but was not baptized yet. At the age of fifteen, he became a soldier at the behest of his father and served in the Roman army.

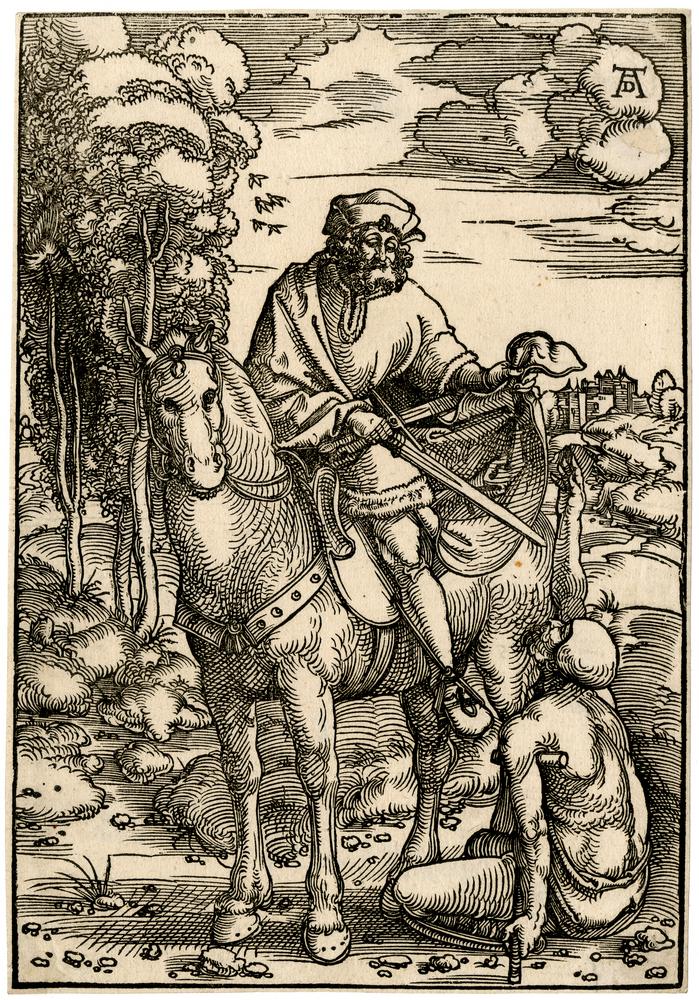

Perhaps the most famous scene from the life of St. Martin occurred during his military service. As he was serving in the army, he encountered a poor, naked beggar man freezing in the cold at the gates of the city of Amiens. Moved with pity but having nothing with him but his sword and his cloak, Martin removed his cloak and cut it in half with his sword, giving it to the beggar man so that he could keep warm. The next night, Christ is said to have appeared to him wearing the half cloak and saying, “Martin the catechumen has clothed me with his robe.” This experience led Martin to be baptized and leave the army.

Martin’s faith and holiness soon came to be known throughout the churches. This reputation ultimately led to his election as bishop of Tours, a position that he was hesitant to accept. According to the story, he had to be convinced to come to Tours on false pretenses, and once he learned that the people wished to make him bishop, he hid in a barn full of geese. Unfortunately for Martin, the geese made such a ruckus in response to the unwelcome visitor that he was found out and made bishop.

While he was visiting Candes, an outlying parish in his diocese, in the year 397, St. Martin fell ill with a great fever. It is said that as he lay dying, he saw an evil spirit who spoke as if he were Christ, a spirit whom Martin had encountered before. He responded, “What do you want, horrible beast? You will find nothing in me that’s yours.” With those final words, he fell asleep in the Lord on November 9. Two days later, he was buried in Tours on the day that would come to be celebrated as his feast day.

A Brief History

Because St. Martin was so well known and beloved in the Church of his own day, the practice of commemorating him and the date of his burial became widespread in Christendom very soon after his death. In fact, the practice of commemorating St. Martin by traveling to his grave in Tours rapidly became so common and widespread that within a century of his death, the bishop of Tours had to build a new, larger church to house St. Martin’s remains.

Over the course of the Middle Ages, St. Martin’s Day—or Martinmas, as it was also called—grew to be one of the most prominent saints’ days of the year, even surpassing the importance of Michaelmas in many places. Consequently, St. Martin’s Day and St. Martin’s Eve were times of great feasting in much of Europe.

But the prominence of Martinmas was not only because of the great popularity of the Bishop of Tours. The feasts of St. Martin’s Day were also related to a feature of the early medieval calendar of the Western Church. In the early Middle Ages, the penitential season of Advent—which now lasts somewhat shorter than four weeks—was a full forty days, much like the other penitential season of Lent. This means that the Advent fast began immediately after St. Martin’s Day, which led many to celebrate Martinmas as somewhat of a Mardi Gras before the Advent season. Eventually, the Advent season was shortened in the Western Church, but the Martinmas feasts remained.

Martinmas is also of particular interest for Lutherans because of another common medieval custom. It became common in many parts of the medieval Church for children to be named after saints whose feast days fell on or close to their birthdays. Consequently, many little boy babies born in early November were named Martin. Thus, it is unsurprising to hear that two of the most famous Martins of the Lutheran Church were born around St. Martin’s Day, with Martin Luther being born on November 10 and Martin Chemnitz being born on November 9.

Collect

Grant, we beseech Thee, O Almighty God: that the solemn feast of Blessed Martin, Thy Confessor and Bishop, may both increase our devotion and further our salvation through the reception of Thy grace; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with Thee and the Holy Ghost: ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Lessons

Epistle

Gospel

Resources

Issues, Etc. interview with the Rev. Will Weedon on St. Martin of Tours

Propers found in Daily Divine Service Book: A Lutheran Daily Missal, edited by the Rev. Heath Curtis

References:

1. Cowie, L. W. and John Selwyn Gummer. The Christian Calendar. G & C Merriam Company. 1974.

2. Parsch, Pius. The Church’s Year of Grace. The Liturgical Press. 1959.

3. Treasury of Daily Prayer. Concordia Publishing House. 2008.

4. Urlin, Ethel L. Festivals, Holy Days, and Saints’ Days. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd. 1915.

Images:

1. St. Martin of Tours, Hans Buldrung, Germany, ca. 1505-1507.

2. Saint Martin of Tours, Miguel March, Spain, ca. 1633-1670.

3. Scenes from The Life of Saint Martin of Tours, Winifred Knights, England, ca. 1928-1933.

[…] prior to the celebration of Easter. In many places, this penitential season began shortly after St. Martin’s Day, making it a forty-day season much like Lent. Over time, however, this season became shorter […]