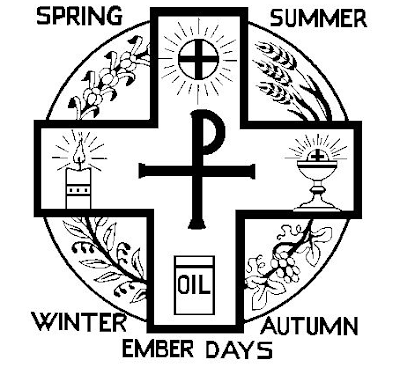

Four times over the course of the Church year, Christians encounter series of three days placed together called Ember Days. Occurring on the Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday following certain seasonal markers, Ember Days are set aside for additional fasting and prayer, thankfulness and assisting those in need. They are also days on which the Church has historically ordained its men for the holy ministry.

These series of days, called Embertides, traditionally take place on the first Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday immediately following these days of the Church’s calendar: St. Lucia’s Day on December 13th for the winter, the first Sunday in Lent for the spring, Pentecost for the summer, and Holy Cross Day on September 14th for the autumn.

The Bounty of Creation

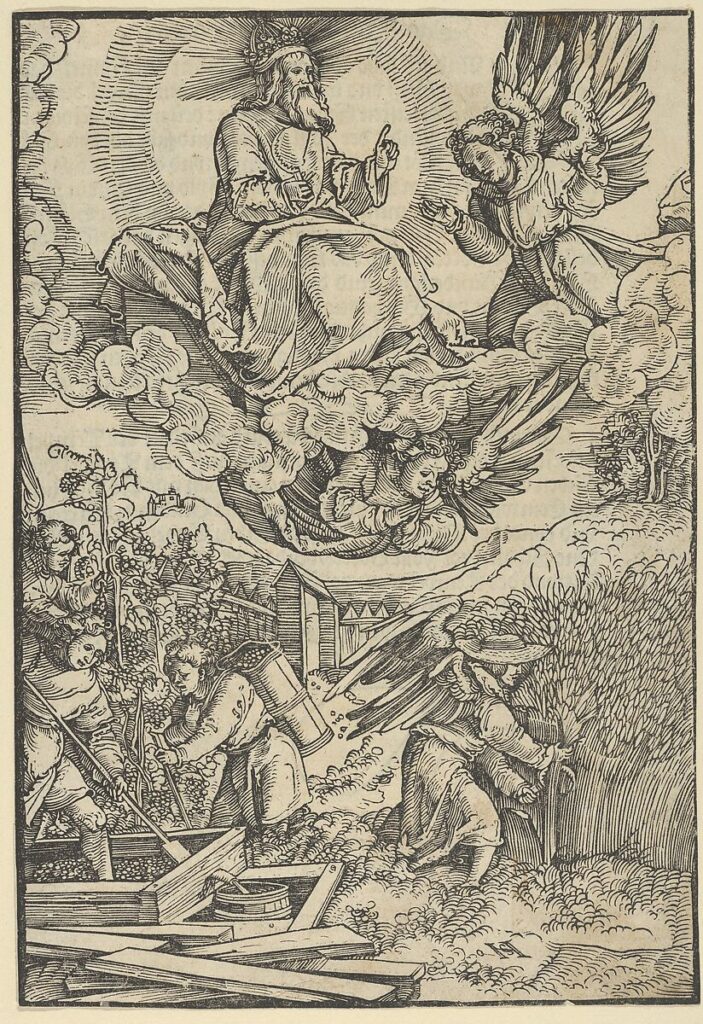

The phrase Ember Days supposedly originates either from the Latin phrase quatuor tempora, or “four times,” or the Anglo-Saxon word ymbryne, which means “cycle” or “round.” The name was used for these days in part because of their conjunction with the harvest periods of the four seasons. It was on these days that Christians originally thanked the Lord for his abundant giving and the blessing of their crops and vocations as well as the bounty of creation. They brought portions of their harvest to the church as an offering, which supported the poor. However, these days’ later association with some of the great feast days of the church became the primary reason for their timing and impetus for their celebration.

As our society’s agricultural focus has decreased, Ember Days have become more and more focused on the Christian themes found within the four seasons. The Ember Days of Advent refer to the coming of Christ; those in Lent refer to the human suffering we endure that is caused by our sin, those of Pentecost reference the descent of the Holy Ghost, and those near Holy Cross Day focus on Jesus’ sacrifice for us.

The History of Embertides

Some variation of the four Embertides has been long observed by the Church, stretching back to the first five centuries of the Christian history and possibly even to the time of the Apostles. Christian historians have also suggested that these periods are a natural post-Jesus Christian evolution of Jewish law, despite the differences between the practices. No matter their origins, though, it is clear that the Christian observance of these days over the history of Christendom has been taken very seriously.

They became part of ecclesiastical ordinance in Rome and from there spread to all areas of the Western Church, making them almost universally practiced within the Western Christian tradition no matter one’s location or cultural background. For example, they were introduced by St. Boniface to Germany and France during his missions there.

Lenty, Penty, Crucy, and Lucy

The Embertides’ placement within the greater Church calendar was also popularized throughout Christendom with various mnemonics so that parishioners could easily remember their occurrence.

In Latin the phrase goes:

Dat crux Lucia cineres charismata dia

Quod sit in angaria quarta sequens feria.

And, in English, an old rhyme states:

Fasting days and Emberings be

Lent, Whitsum, Holyrood, and Lucie.

Over time this was also adapted to the rhyme:

Lenty, Penty, Crucy, and Lucy.

Traditional Customs

Besides their association with various Christian holidays, each of the Embertides’ correlation with certain harvests of the year—winter = olives, spring = flowers, summer = wheat, and autumn = grapes—also gave rise to a variety of ways in which these days came to be celebrated within the Church. Further, thankfulness for the specific seasonal bounties became liturgically important as each of these harvests relates to the life of the Church: the olives of winter make oils, the flowers of spring feed the bees that make wax used for candles, the summer wheat turns into bread, and the autumn grapes turn into wine.

As you can imagine, these symbols have provided many opportunities for Christians to commemorate the Ember Days and the ways in which the specific seasonal harvests correlate to the life of the Church.

First comes the invention of Ember, or Ymbryne, tarts, which date back as far as the twelfth century and were simple dishes well suited for the fasting season. Although they could be made several different ways, an onion and egg tart was an especially popular choice.

Second, a well-known Ember Day custom was popularized by the invention of Japanese tempura in the sixteenth century when Spanish and Portuguese missionaries settled in Nagasaki. Deriving its name from the Latin phrase, quatuor tempora, the meaning of which we broke down above, this culinary style provided a unique twist on the typical fasting foods.

Third was the seasonal focus on the aforementioned harvest of foods. Depending on which Embertide was being commemorated, Christians would make a meal and set a table centered around foods like olives, honey, wheat, and grapes, using the opportunity to thank God for his gifts of these bounties to his people.

Last, the praying of the Litany was a usual and expected custom of Ember Days, focusing the Church and her people on repentance and taking time out of each season to slow down and listen to God’s Word.

Lutherans and Ember Days

Because of the importance that these days always have had in the Church, Lutherans have long commemorated Ember Days with fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. It has only been more recently, with the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, that these practices have fallen out of style with Roman Catholics and, unfortunately, the rest of the Christian world. As some have said, “When Rome catches a cold, Lutherans sneeze.”

Due to these changes across culture, many Lutherans today are less familiar with Ember Days than they were before, even though they still remain a vital part of the Christian historic tradition. Indeed, these days are not just for the liturgical extremists but are rather useful for all Lutherans to remember. They are valuable to the Christian calendar insofar as they provide us with the opportunity to focus on repentance.

Some congregations will offer individual confession and absolution on one or more of these days. In the days of the Reformation, Embertides marked a time in which the clergy especially focused on preaching the Catechism. Thus, they became a time set aside four times a year to give special attention to the catechismal basis and fundamentals of Christian knowledge. Both historically and today, Ember Days usually include days on which Christians pray the Litany and focus on “humiliation and prayer.”

As we reflect on the foci of these Ember Days and quickly approach one of the Embertides of the year, both of us at All the Household encourage you to think more about these days’ historical place and usage in the Church. Consider the ways in which this aspect of the Church’s calendar and liturgy might be worth resurrecting in your own household, social group, or parish!

Continued Reading

Braden, Mark. “Taking Pains: Rogation Days and Ember Days.” 2014.

Kellner, Karl Adam Heinrich. Heortology; A History of the Christian Festivals from their Origin to the Present Day. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner, and Co. 1908.

Kinnaman, Scot. “What are Ember Days?” 2009.

Kinnaman, Scot. “Winter/St. Lucy Ember Days Soon Upon Us.” 2010.

Treasury of Daily Prayer. Concordia Publishing House. 2008.

Vitz, Evelyn Birge. A Continual Feast. Ignatius Press. 1985.

[…] Ember Days might be an unfamiliar celebration to some of us, their placement next to feasts of the Christian […]