“To Dust You Shall Return”

Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of the Lenten journey, the church’s forty-day period of intense fasting and inner preparation that readies us to keep the feast of our Lord’s death and resurrection in sincerity and truth. As the beginning of Lent, Ash Wednesday reminds us: you are going to die, so repent.

“You are dust, and to dust you shall return,” are often the first words those in attendance on Ash Wednesday hear as they walk into the nave and receive ashes on their forehead. These words of God’s curse to Adam harken back to the very beginning. God formed Adam from the dust, breathed the breath of life into him, placed him in the garden, and set all of creation before him except for that forbidden tree. Disbelieving, Adam took the forbidden fruit and would now surely die. Without the breath of life, Adam must return to the dust. This is the fate of all people, and the imposition of ashes on Ash Wednesday confronts us with this truth “head-on.” We, too, must die.

But ashes are not just a symbol of death and the curse. Ashes belong to the repentant. Take the case of the people of Nineveh who receive Jonah’s admonition and turned from their evil ways. They repented in ashes and sackcloth (3:5). Daniel and Job acted similarly in their own times. God sees the sackcloth and ashes of the repentant, for “a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise” (Psalm 51:17). Our Lord takes up this point in Matthew—if his deeds had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented in sackcloth and ashes (Matthew 11:21)!

As the day’s collect reminds us, God does not despise anything he has made but forgives the sins of all who are penitent. Here comes a third meaning behind the ashes: in Numbers, the Lord instructs Moses and Aaron to collect the ashes of a burned heifer mixed with water as a sin offering. See how the ashes are used in pardoning sin, a practice continued by the Church and recorded as early as the third century. A little later, Eusebius also describes the rite of pouring ashes over the head of penitents following their confession.

The confrontation we experience with our mortality and sinfulness lead us to the gospel text. It comes from Matthew’s account of the Sermon on the Mount when Jesus follow’s Moses’ steps up a mountain, but bringing the people with him, he sits down and opens his mouth to teach. “When you give… When you pray… When you fast…” He instructs the people in the posture of the Christian. These lessons are given to those who have repented, been cleansed, and now walk in a new way, thus beginning the Lenten journey.

A Brief History

We’ve already established that the use of ashes together with repentance reaches as far back in history as the Old Testament. Tertullian in the second century is among the first after the apostolic age to describe the use of ash and sackcloth, and Eusebius describes the rite of pouring ashes over the head of penitent following their confession.

The day of ashes also appears early in Christian history, certainly as early as the eighth century and in some form or another even before that. One early reference comes from a service book of the Gregorian rite which describes a Day of Ashes. The season of Lent has been sometimes longer and other times shorter, but Ash Wednesday seems to have taken root as the beginning of the season in the eighth century, when the forty-day period, excluding Sundays, rapidly became the standard, recalling especially Jesus’ forty-day fast in the wilderness but also the Israelites’ forty-year wandering and Moses’ forty days on Mount Sinai.

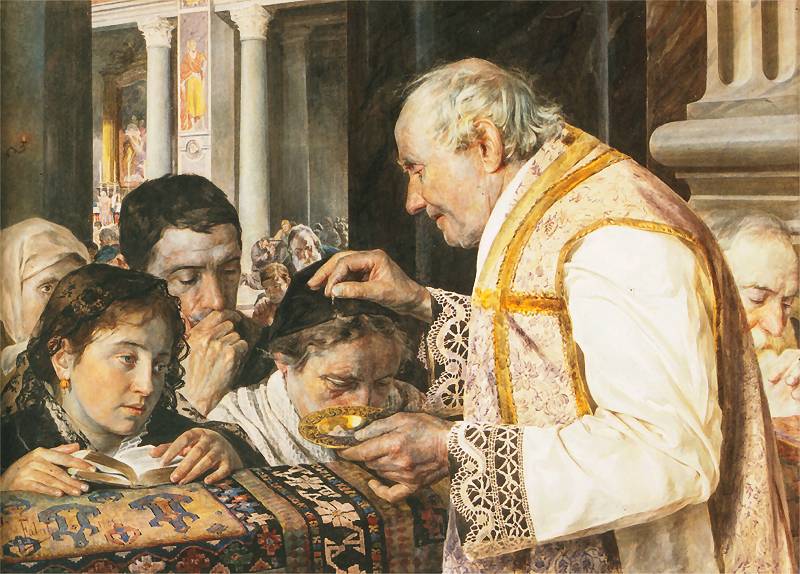

But at the origins of Ash Wednesday, the practice of receiving ashes was not always for everyone. The imposition of ashes was only for those who were cast out of the church on Ash Wednesday until their fasting and penance was complete. These were specifically those who had turned away from the faith and now repented or committed grievous public sins. Their status under church discipline was public, so they bore the public symbol of ashes while absent from the communion of saints until they were received back into the church in the first service on Maundy Thursday. By the eleventh century, the observance expanded to all Christians, and all received the imposition of ashes and followed along in the catechetical and penitential spirit of Lent.

Since the time of the Reformation, the Lutheran church has retained Ash Wednesday but has been careful to place the emphasis in the right place: first, on Christ and his atoning sacrifice. The disciplines of fasting, almsgiving, and prayer are not imposed for the sake of salvation but are “undertaken as an exercise in faith and love” and “serve to cleanse the Christian life and facilitate the fruits of repentance” (Stuckwisch).

But for Lutherans and Protestants, the imposition of ashes often fell out of practice because of the apparent contradiction with the day’s Gospel text: when you fast, do not disfigure your face to be seen by others (Matt 6:16). While the history is complicated, the imposition of ashes was still held by Luther and many other Lutherans in history to be an acceptable practice that is done not for one’s own glory but out of piety and in submission to the Father which Christ does not forbid. By the twentieth century, this practice was widely restored where it had falled into misuse and is now observed in Lutheran churches across the country. It remains a matter of Christian freedom.

Collect

Almighty and Everlasting God, who hatest nothing that Thou hast made and dost forgive the sins of all those who are penitent: create and make in us new and contrite hearts, that we, worthily lamenting our sins and acknowledging our wretchedness, may obtain of Thee, the God of all mercy, perfect remission and forgiveness; through Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with Thee and the Holy Ghost: ever one God world without end. Amen.

Lessons

Resources

The Gottesdienst Crowd interview with the Rev. Mark Braden on Ash Wednesday

Propers found in Daily Divine Service Book: A Lutheran Daily Missal, edited by the Rev. Heath Curtis

References:

1. Lutheran Service Book: Companion to the Services. Edited by Dr. Paul Grime. Concordia Publishing House. 2022.

2. Pfatteicher, Philip H. Journey into the Heart of God. Oxford University Press. 2013.

Images:

1. Hypocrite and a believer during fasting, Christopher van Shechem (II) after Karel van Mallery after Bernardino Passeri, Netherlands, 1629.

2. Ash Wednesday, Julian Fałat, Poland, 1881.

3. Initial D at beginning of prayer during the blessing of ashes on Ash Wednesday, Missal of Eberhard von Greiffenklau, Netherlands, 15 century.

4. The Battle Between Carnival and Lent, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Belgium, 1559